Nureyev is an astonishing testament to the motion in motion pictures. Written and directed by Jaqcui Morris and David Morris, this documentary saves the phenomenon and life force of one of 20th century greatest ballet dancers and—also—pop icon, Rudolph Nureyev from the oblivion of history. In combining narration and archive footage with danced and dramatized elements of his life story, further enhanced by an affective musical score, Nureyev succeeds in conveying the ephemeral quality of dance and how it, at its best, moves even the stationary viewer. (MJJ: 4.5/5)

Review by FF2 Associate Malin J. Jornvi

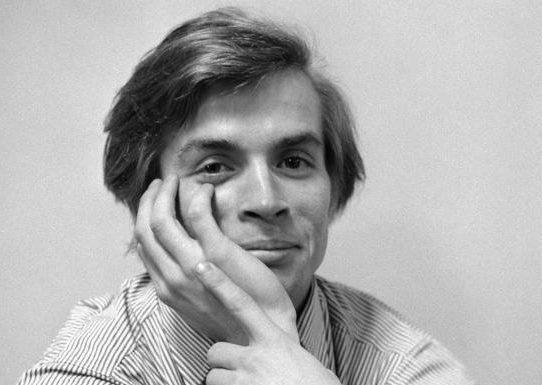

Jaqcui Morris and David Morris have directed a documentary at its fullest: Nureyev is a picture that makes complete use of the art form and clearly shows the filmmakers’ passion and urgent need to tell a story. It is a documentation of the Russian ballet dancer Rudolph Nureyev, a figure quite unknown in current pop culture, but as Nureyev illustrates, this was not quite the case in the 60-80s. For if the contemporary viewer finds it hard to imagine a ballet dancer to also be one of the most controversial sex icons in popular press, once having seen Nureyev, one cannot help but to understand why.

The documentary succeeds in the tricky feat of giving a thorough account for the dramatic life story of Rudolph Nureyev—from his birth on a Trans-Siberian railroad to his dignified farewell at the Paris Opera—without making it too heavy or dragging. Frankly, this documentary is very much the opposite: Nureyev moves throughout. The drive of the picture is to a large extent thanks to the enthralling combination and layering of archive images together with the select aspects of his life that are enacted and choreographed in new footage. The live quality is also due to the affective musical score which runs along the documentary’s 1 hour and 49 minutes and invites further access to and resonance with the narrative.

Rudolph Nureyev was born in USSR in 1938 and was already a well-known international star when he defected in 1961 and went on to become a 1980s gay symbol. His life thus spans across many major events of the 20th century, a history especially tinted by the Cold War and the Iron Curtain. In retelling Nureyev’s story, the political history becomes intimately personal and Jaqcui Morris and David Morris makes an impressive use of the potent blend.

But Rudolph Nureyev’s story is also a history of creative geniuses, and this is one aspect which the documentary could have problematized more. Nureyev is insistently described as a lion or a panther yet it is only towards the end of the picture that a few words are mentioned regarding his self-proclaimed “Tatar blood.” It is also only briefly noted that it was his assistants backstage that were the ones to fully experience the physical side of this passion. Another unproblematized thread is the inclusion of multiple rather questionable quotations. For example, the documentary opens with the words of Napoleon Bonaparte: “Great people are meteors designed to burn so that the earth may be lighted.” Surely playing on Nureyev’s temperament and though definitely thought-provoking, the quotes and the casual take on aggressive artists could have been more nuanced and modern.

Still, Nureyev is a multi-layered and complex piece and the many recorded comments by former dance partners and historians add to the comprehensive impression. Nureyev’s most famous collaboration was with Prima ballerina and Dame Margot Fonteyn and a large part of the documentary covers their relationship. But instead of dwelling on their being versus not being lovers, Jaqcui Morris and David Morris move beyond and spend time on Fonteyn and her historical and artistic footprint. Her marriage to Roberto “Tito” Arias is woven into the narrative which further speaks to the directors’ broader historical claim. It is also a fine illustration of how art is never “just” art, but always part of a larger cultural context. This becomes especially evident right at the final minutes of the documentary when the filmmakers abruptly and efficiently switch approach and straight forwardly declare the fact that AIDS did not die with Rudolph Nureyev. Indeed, in contrast to what Western media likes to believe, AIDS is still directly lethal in many parts of the world: “AIDS has not gone away.” The proclamation is a sober and real reminder of how we, like Nureyev, are trapped in a cultural and political web much larger than ourselves—an aspect which at least Nureyev himself never stopped fighting.

Rudolph Nureyev was finally able to revisit Russia and his family after 28 years in exile, just before his mother’s death. Another woman who played a crucial role in shaping the world famous dancer was Nureyev’s first ballet teacher and perhaps the most moving image of all in Nureyev is the video from his hometown visit which shows his reunion with the more than 100 years-old dance teacher. The sequence is an example of the possible dimensions provided by the documentary style compared to fictive drama and the temporal limits put by a narrative arc: Nureyev’s story has recently been directed by Ralph Fiennes in The White Crow. But compared to the Hollywood version, the documentary about Nureyev shows that a life, any life, cannot be reduced to a single storyline. Instead, as Nureyev so effectively illustrates, and as Nureyev himself so astoundingly conveyed through his body: life moves in so many directions at once and the real art is to take the chaos and to move with it.

© Malin J. Jornvi (13/6/19) FF2 Media

Photo Credits: CineLife Entertainment

Q: Does Nureyev pass the Bechdel-Wallace Test?

No.

However, the B-W test is always difficult to apply to documentaries without dialogue.

Your article has answered the question I was wondering about! I would like to write a thesis on this subject, but I would like you to give your opinion once 😀 majorsite